MicrobeGrower

Beyond the Soil Test: Understanding the Living System Beneath Your Feet

Science-backed insights on soil biology, regenerative agriculture, and building living soil systems that reduce inputs while increasing yields.

More Than Mud: The Secret Life of Your Soil and How to Feed It

The soil ecosystem operates through specialized microbial guilds, each performing distinct ecological functions:

Unlocking Clay Soils: The Science of Flocculation and Calcium Management

When clay platelets lie flat against one another in tightly packed arrangements—a condition called dispersion—the microscopic pore spaces essential for air and water movement effectively disappear. Oxygen cannot penetrate to support root respiration or aerobic microbial activity.

Powdery Mildew Defense: Building a Living Fungal Shield Through Foliar Biology

Conventional fungicide programs require continuous investment with no reduction over time as resistance develops. Biological approaches involve lower long-term direct costs. Once beneficial populations establish, application frequency typically decreases while effectiveness increases, creating improving economics over successive seasons.

Natural Aphid Control: Building Your Garden's Defense Team

The sustainable solution lies not in sprays and chemicals, but in cultivating the natural predators that have controlled aphid populations for millions of years. By understanding and supporting these beneficial organisms, you can establish a self-regulating system that maintains aphids at manageable levels without constant intervention.

- Dec 30, 2025

The Living Solution to Clay Soil Compaction: How Soil Biology Creates Lasting Structure

Clay soils present a paradox for agricultural producers and gardeners alike. When properly managed, these soils offer exceptional nutrient retention, water-holding capacity, and long-term fertility that can sustain productive systems for generations. Yet when mismanaged, these same soils become nearly impenetrable barriers—waterlogged during wet periods, concrete-hard when dry, and hostile to root development and soil biological activity throughout the growing season.

The conventional response to clay soil problems has focused almost exclusively on chemical amendments: tons of gypsum, truckloads of lime, and repeated applications season after season. While these inputs provide temporary relief, they address symptoms rather than root causes. The calcium-to-magnesium ratios may shift on paper, but the underlying biological dysfunction that created the structural problem remains unresolved. Worse, dependence on calcium amendments creates an expensive, perpetual input cycle that never truly solves the problem. /

The transformative solution lies not in bags and trucks but in the soil itself—specifically, in cultivating the diverse microbial communities that evolved over millions of years to create and maintain soil structure naturally. Understanding and supporting these biological processes represents the difference between temporary symptom management and genuine, lasting soil regeneration.

Why Chemical Amendments Are Band-Aids, Not Solutions

The agricultural industry has long promoted calcium amendments as the primary answer to clay soil compaction and poor structure. Gypsum applications, lime spreading, and calcium-based fertilizers generate substantial revenue streams, creating financial incentives to perpetuate chemical-dependent management approaches. Yet honest assessment of long-term results reveals serious limitations.

Chemical amendments provide temporary mechanical spacing of clay particles through cation exchange, but this effect degrades continuously. Rain events, irrigation cycles, and natural cation displacement gradually erode the calcium saturation that creates particle separation. Within months to a few years, calcium levels decline, magnesium ratios shift, and structural problems return—prompting another round of expensive amendments. The cycle repeats indefinitely, with costs accumulating and the fundamental problem never resolving.

More problematically, heavy calcium amendment programs can actually suppress the biological activity essential for lasting soil health. Excessive calcium applications disrupt nutrient balance, creating induced deficiencies of other essential elements. The sulfate in gypsum, while providing some benefit, can suppress mycorrhizal colonization when applied at high rates. Most significantly, focusing management attention on chemical ratios diverts resources and energy away from the biological interventions that create self-sustaining soil structure.

Clay soils managed primarily through calcium amendments remain biologically impoverished—dependent on continuous inputs to maintain minimal function. When amendment programs are interrupted by economic constraints, supply disruptions, or management transitions, soil structure rapidly deteriorates because no biological foundation exists to maintain it.

This is not to suggest calcium has no role—adequate calcium availability supports both plant health and microbial function. However, positioning calcium amendments as the primary solution represents fundamentally flawed logic that keeps producers locked in expensive input dependency while preventing genuine soil regeneration.

The Biological Architecture of Clay Soil Structure

Healthy clay soils in natural ecosystems—prairies, forests and undisturbed grasslands—exhibit remarkable structure despite receiving no calcium amendments, no gypsum applications, and no lime spreading. These soils readily absorb heavy rainfall, support deep root systems, and maintain stable structure across seasons. The difference between these functional soils and problematic agricultural clays is not calcium-to-magnesium ratios but biological activity.

Soil structure in natural systems is created and maintained by an integrated community of organisms working at multiple scales. Understanding these biological mechanisms reveals why supporting soil life provides superior long-term solutions compared to chemical amendment dependency.

Bacterial polysaccharides form the primary binding agent in soil aggregation. Bacteria, particularly those in the Rhizobium, Azotobacter, and Bacillus groups, secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) as they metabolize organic matter. These sticky compounds—complex sugars and proteins—act as biological glues that bind individual clay particles into microaggregates. Unlike calcium's electrostatic spacing effect, bacterial polysaccharides create physical bonds that resist disruption from rainfall impact, wetting-drying cycles, and mechanical disturbance.

The volume of polysaccharide production correlates directly with bacterial population density and activity levels. Soils with active bacterial communities measuring 300-500 million organisms per gram consistently demonstrate superior aggregation compared to depleted soils, regardless of calcium levels. This biological production represents free, continuous structural improvement that intensifies over time as organic matter accumulation feeds expanding bacterial populations.

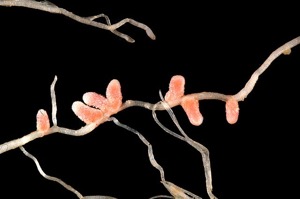

Fungal hyphae provide the structural framework that transforms microaggregates into stable macroaggregates. Fungal networks, particularly saprophytic fungi and arbuscular mycorrhizal species, physically enmesh soil particles with thread-like hyphae ranging from 2-20 micrometers in diameter. These hyphal networks create the macropore structure essential for air and water movement through clay soils.

The mechanical strength of fungal hyphae proves critical for clay soil management. Hyphae can exert pressures exceeding 1000 pounds per square inch as they grow, physically forcing apart compacted soil particles. A single gram of healthy soil contains several meters to several kilometers of fungal hyphae—an enormous structural network that no amount of calcium can replicate. As hyphae grow, decay, and regenerate continuously, they create ever-expanding networks of stable pore space through previously compacted zones.

Mycorrhizal fungi provide additional benefits beyond structural improvement. Their symbiotic relationships with plant roots dramatically enhance phosphorus acquisition—particularly valuable in clay soils where phosphorus fixation creates chronic deficiency despite adequate soil test levels. By improving phosphorus availability biologically, mycorrhizal colonization reduces or eliminates phosphorus fertilizer requirements while simultaneously building soil structure.

Earthworms and soil fauna represent the visible engineers of soil structure. Earthworm populations in healthy clay soils can exceed one million individuals per acre, collectively processing tons of soil and organic matter annually. Earthworm burrows create permanent macropores that facilitate rapid water infiltration and deep root penetration. Perhaps more importantly, earthworm casts—the processed soil excreted by earthworms—exhibit aggregation and stability far superior to surrounding bulk soil, with aggregate stability lasting for years after formation.

The mucus secreted by earthworms contains polysaccharides and proteins that powerfully promote aggregation. Research demonstrates that earthworm casts contain 5-10 times more water-stable aggregates than adjacent soil, with this stability persisting through multiple wet-dry cycles. A single earthworm can produce its own weight in casts every day, representing substantial ongoing structural improvement.

Soil arthropods—including springtails, mites, and various insects—contribute by shredding organic residues, creating additional pore spaces through their movements, and supporting microbial activity through their feeding and excretion. The cumulative effect of diverse soil fauna creates structural complexity that chemical amendments simply cannot achieve.

Specific Microbial Groups for Clay Soil Regeneration

While general biological activity improves clay soil structure, certain microbial groups provide disproportionate benefits for flocculation and aggregation. Targeting management practices to support these organisms accelerates structural improvement and creates resilient soil function.

Nitrogen-fixing bacteria play surprisingly important roles beyond nitrogen provision. Free-living species including Azotobacter and Azospirillum produce exceptional quantities of polysaccharides during nitrogen fixation, with some strains secreting polysaccharides equal to 50% of the carbon they metabolize. These organisms proliferate in the presence of fresh organic matter and adequate moisture, creating pulses of aggregate-forming compounds that bind clay particles into stable structures.

Symbiotic nitrogen fixers like Rhizobium species contribute through their association with legume roots. The copious root exudates produced by actively fixing legumes feed expansive bacterial populations in the rhizosphere, with these bacteria producing the polysaccharides that improve aggregation throughout the root zone. Strategic use of legume cover crops specifically stimulates these beneficial organisms while simultaneously building nitrogen reserves—addressing two critical soil health parameters with a single practice.

Actinomycetes represent a bacterial group particularly valuable for clay soil management. These filamentous bacteria produce branching networks similar to fungal hyphae while secreting powerful enzymes that decompose complex organic compounds. Actinomycetes thrive in neutral to slightly alkaline clay soils, where their populations can exceed 10 million per gram. Their characteristic earthy smell indicates active populations transforming organic matter into humus—the most stable form of soil organic matter and a critical component of long-term structural improvement.

Actinomycete populations respond strongly to compost incorporation and surface mulching, with mature compost often containing concentrated populations that inoculate soil when applied. These organisms also produce antibiotics that suppress root pathogens—providing disease resistance benefits alongside structural improvement.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) form symbioses with approximately 80% of terrestrial plants, including most agricultural crops. AMF hyphae extend 10-100 times beyond root surfaces, dramatically expanding the effective root system while producing glomalin—a glycoprotein compound that represents one of the most powerful soil aggregating agents identified. Research indicates glomalin can constitute 15-20% of soil organic carbon in healthy grasslands and contributes substantially to water-stable aggregation.

AMF populations collapse under conventional management practices, particularly tillage and high phosphorus fertilization. Reestablishing robust AMF networks requires reducing tillage intensity, maintaining living roots throughout the year through cover cropping, and avoiding excessive phosphorus applications that suppress colonization. Once established, AMF populations self-perpetuate and expand, creating progressive structural improvement that intensifies with each growing season.

Saprophytic fungi including various Trichoderma, Penicillium, and Aspergillus species decompose complex organic materials while producing extensive hyphal networks. These fungi prove particularly valuable for incorporating crop residues and cover crop biomass, transforming surface organic matter into soil structure throughout the profile. Their rapid growth rates and aggressive colonization characteristics make them pioneer organisms that initiate biological recovery in depleted soils.

Practical Management: Cultivating Structural Microbes

Building and maintaining the microbial communities that create lasting clay soil structure requires integrated management focused on feeding and protecting soil biology. These practices generate compounding returns as biological populations expand and soil function improves progressively over time.

Continuous living roots provide the primary energy source that drives soil biological activity. Plant roots exude 20-40% of photosynthetically fixed carbon directly into soil—a massive energy subsidy specifically targeted to the rhizosphere where aggregation matters most. Maintaining living roots throughout the year through cover cropping, perennial integration, or extended crop rotations sustains microbial populations that would otherwise decline during fallow periods.

Cover crops provide multiple structural benefits simultaneously. Deep-rooted species physically fracture compacted layers while feeding rhizosphere biology. Diverse species mixes support broader microbial communities than monocultures. Legume inclusion specifically stimulates nitrogen-fixing bacteria that produce aggregating polysaccharides. Winter covers protect existing soil structure while continuously feeding organisms that maintain and enhance aggregation.

The economic logic of cover cropping proves compelling for clay soil management. Rather than purchasing calcium amendments annually, producers invest in seed that generates biological activity worth thousands of dollars in structural improvement while simultaneously building nitrogen reserves, suppressing weeds, and improving water infiltration. The practice pays for itself through reduced inputs while creating lasting soil improvement.

Compost application delivers concentrated microbial populations directly to soil while providing the organic matter substrate these organisms require. Quality compost contains billions of beneficial bacteria and millions of fungal propagules per gram—serving as both inoculant and food source. The aggregating effects of compost prove particularly dramatic in clay soils, where even modest application rates (1-2 tons per acre) produce measurable structural improvement.

Compost selection matters significantly. Thermophilically-produced compost from diverse feedstocks provides the broadest microbial communities and most stable organic matter. Fungally-dominated composts—achieved through extended curing periods with high carbon materials—deliver superior structural benefits compared to bacterially-dominated materials. Local production from on-farm residues transforms waste materials into valuable biological amendments while eliminating purchase and transportation costs.

Minimizing tillage intensity protects the fungal networks and earthworm populations that create macroaggregate structure. Each tillage pass destroys kilometers of fungal hyphae per acre, disrupts earthworm burrows, and exposes organic matter to accelerated decomposition. The structural damage from tillage events requires weeks to months for biological recovery—time during which soil remains vulnerable to compaction and erosion.

Transitioning toward reduced tillage or no-till management preserves biological structures while allowing progressive improvement. Strip-tillage provides an intermediate approach that concentrates soil disturbance in crop rows while leaving inter-row areas undisturbed for biological development. The structural benefits of reduced tillage become increasingly apparent over successive seasons as fungal networks expand, earthworm populations recover, and macropore systems develop throughout the soil profile.

Diverse crop rotations support broader microbial communities than monoculture systems. Different crops associate with distinct mycorrhizal species, support different bacterial populations, and produce varying root exudate chemistry. Rotation diversity prevents population crashes of beneficial organisms while suppressing specialist pathogens. Including both grasses and broadleaves, shallow and deep-rooted species, and crops with contrasting resource demands maintains balanced biological communities capable of creating and sustaining optimal soil structure.

Eliminating biological suppressors proves as important as adding biological stimulants. Fungicides and bactericides directly kill beneficial organisms along with target pathogens. High-rate synthetic nitrogen applications suppress nitrogen-fixing bacteria and reduce mycorrhizal colonization. Excessive tillage destroys fungal networks and disrupts earthworm populations. Bare soil periods starve rhizosphere organisms. Each of these practices undermines the biological communities essential for structure, creating dependency on chemical amendments as biology declines.

The Economics of Biological vs. Chemical Structure Management

Comparing biological and chemical approaches to clay soil structure reveals dramatic differences in both short-term costs and long-term trajectories. Chemical amendment programs require continuous inputs—gypsum or lime applications every 1-3 years indefinitely. At typical rates (1-2 tons per acre) and current prices, annual costs range from $100-300 per acre solely for structural management, with no reduction over time and no residual benefit beyond temporary mechanical spacing.

Biological structure development involves front-end investment in practices—cover crop seed, compost production or purchase, equipment modifications for reduced tillage—that generate expanding returns over subsequent seasons. Cover crop costs ($30-60 per acre annually) decrease as producers gain experience with species selection and establishment while benefits compound through biological population expansion. Compost applications (one-time or periodic) create lasting improvement rather than temporary effects. Reduced tillage decreases fuel and equipment costs while biological populations expand.

Most significantly, biological structure improvement creates system-wide benefits beyond the specific structural outcomes. Enhanced nitrogen fixation reduces fertilizer costs. Improved phosphorus availability through mycorrhizae decreases phosphorus input requirements. Disease suppression from diverse soil biology reduces pesticide needs. Increased water infiltration and retention improves drought resilience. These cascading benefits transform clay soil management from an isolated input expense to an integrated investment in overall soil function.

The long-term trajectory favors biological approaches decisively. Chemical amendment dependency continues indefinitely with no exit pathway—costs persist or increase over time. Biological development reaches self-sustaining states where minimal management maintains excellent structure through the natural activity of established microbial communities. This represents genuine soil regeneration rather than perpetual symptom treatment.

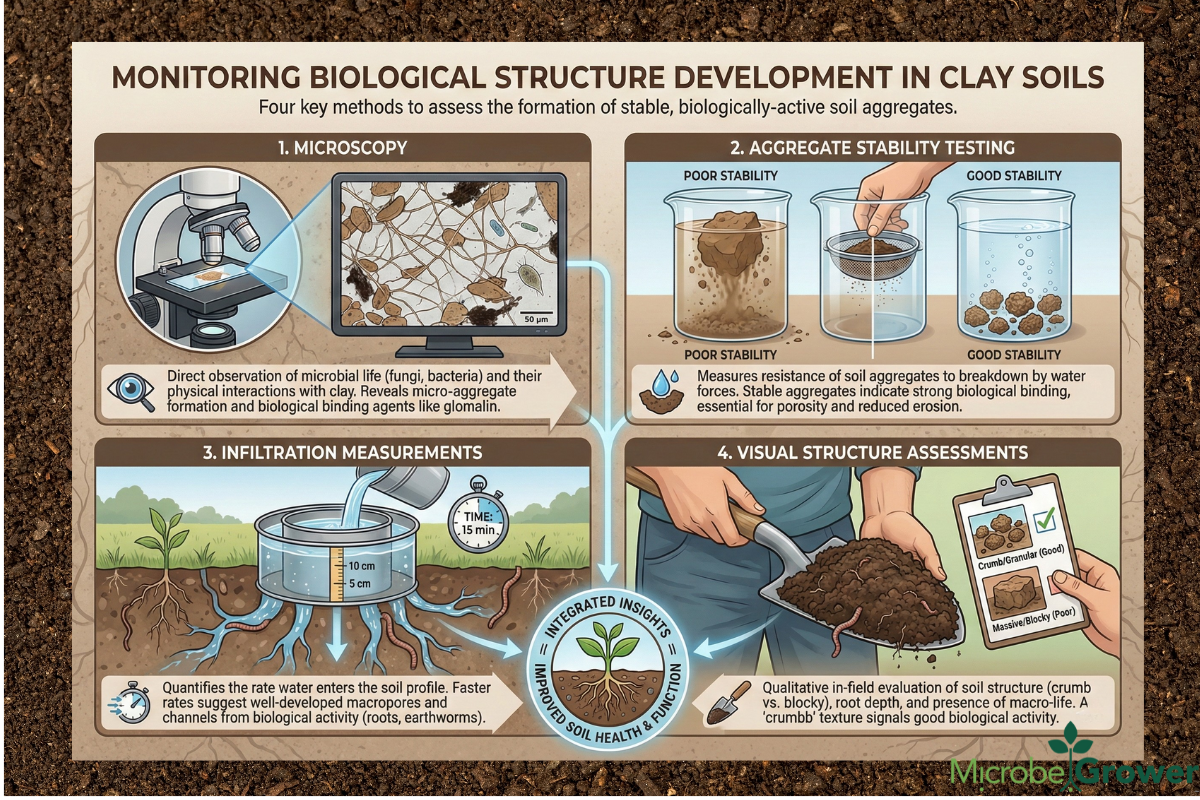

Monitoring Biological Structure Development

Assessing biological structure improvement requires different indicators than chemical monitoring. While soil testing for calcium and magnesium ratios reveals chemical status, these numbers provide limited insight into actual structural function or biological activity. More meaningful assessment focuses on direct observation of biological populations and functional outcomes.

Microscopy provides direct visualization of the microbial communities creating structure. Simple compound microscopes (400-1000× magnification) reveal bacterial populations, fungal hyphal density and characteristics, and protozoan activity—the organisms directly responsible for aggregation. Observing diverse, active populations confirms that structural improvements will follow. Tracking population changes over seasons documents management effectiveness and guides practice adjustments.

Aggregate stability testing measures the functional outcome of biological activity. The slake test—observing how soil aggregates behave when submerged in water—provides immediate qualitative assessment. Biologically-bound aggregates remain intact while chemically-bound or unbonded particles disperse. Quantitative aggregate stability testing through laboratory analysis documents progress and enables comparison across management approaches or time periods.

Infiltration measurements demonstrate practical structural function directly relevant to crop production. Simple infiltration rings reveal how quickly water enters soil—the outcome that matters for managing rainfall, reducing runoff, and supporting crop water needs. Improvements in infiltration rate indicate successful structural development regardless of specific calcium levels or microbial population numbers.

Visual structure assessment remains accessible to every producer. Well-aggregated soil exhibits granular or crumb structure visible to the naked eye. When moistened and handled, biologically-aggregated soil forms soft, friable material that crumbles readily rather than smearing or forming plastic masses. Root penetration, earthworm burrow density, and the presence of fungal hyphae visible on organic residues all indicate active biological structure formation.

Build Living Soil Structure: Expert Biological Consultation

1. Comprehensive Soil Biology Assessment & Regeneration Protocol

Discover exactly what's living (or missing) in your clay soil through detailed microscopy analysis, aggregate stability testing, and functional assessment. Receive a customized biological management plan specifically designed to cultivate the microbial communities your soil needs for lasting structural improvement. This consultation includes soil sampling and analysis, written recommendations with cover crop species, compost protocols, and tillage modifications tailored to your operation. [Schedule Your Biological Assessment]

2. Soil Microscopy Training & On-Farm Biology Workshop

Learn to see and understand the microorganisms creating soil structure on your land. This hands-on workshop teaches proper microscope technique, organism identification, and interpretation of biological indicators for management decisions. You'll examine your own soil samples, learn what to look for throughout the season, and gain the skills to monitor biological development independently. Includes follow-up support as you implement biological practices. [Book Your Microscopy Training]

3. Year-Long Biological Structure Optimization Program

Work directly with a soil biology specialist to systematically build microbial communities and soil structure throughout a complete growing season. This intensive program includes baseline microscopy and testing, customized cover crop and compost recommendations, quarterly on-farm evaluations with real-time microscopy, and continuous consultation access for questions and adjustments. Limited availability for producers committed to biological regeneration. [Apply for Annual Program]

Stop treating symptoms with endless calcium applications. Build the living soil biology that creates permanent structural solutions while simultaneously reducing costs and improving overall soil health.